Convictions of the widest range were made during the nineteenth century, convictions ranging from stealing loaves of bread to murder. No matter their extent, many of the convicts who were sent to the distant land of Australia chose to memorialise themselves in tiny tokens of copper.

For the convict Thomas Alsop, it was the token he gave to his mother which signified his leave as a consequence of stealing a sheep [1]. He had it commissioned due to his inability to read or write with two statements [1]. The first on the front, which captions an image of a ship reads ‘Accept this dear Mother from your unfortunate son -Tho Alsop- Transported July 25 Aged 21 1833’. Then the second on the back shows a rhyme, which reads ‘The rose soon drupes & dies. the brier fades away. but my fond heart for you I love shall never go astray’ [1]. It is in this token particularly, that we can see the extent that many convicts would go to to create something that had a piece of themselves in it for their loved ones to remember them by. For Alsop, the careful details that were considered when this was made is far beyond many of the others, however what might make this slightly less impressive is that he cannot read or write, so the small rhyme is more likely to have been someone else’s helpful touch. And according to the National Museum of Australia, Alsop actually had at least two tokens made, one for his mother and one for an unknown person which is kept in a private collection [1].

http://www.maritimetas.org/collection-displays/displays/over-seas-stories-tasmanian-migrants/convict-colony

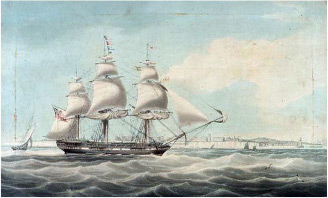

Now to really delve into Mr. Alsop. Banished to Van Diemans Land in 1834 with a life sentence and transportation aboard the Moffatt, a ship with the capacity to carry up to 400 convicts in one journey between 1834 and 1842 [2], easily one of the biggest convict carriers built. Upon further research Alsop, which is also spelt ‘Allsop’ in other records [2] [3], gave into another type of prison ‘micro-narrative’, tattoos. Sharing a ‘similarity in sentiment’ (Donnelly, p.38) [7] to the love token, the purpose of getting tattoos for prisoners was to solidify their identity whilst being sentimental. Even though the tokens were seen as a more feminine departing gift, tattoos had more connotations of masculinity and bravado due to the pain endured during the tattooing process. Furthermore, they made it extremely easy to identify bodies it they had been lost at sea or killed, which was an idea originally adopted by sailors [5]. In fact they were considered such an important identifying factor that convict records made note of whether or not convicts had tattoos and what they were. In Alsop’s case, he had a mermaid inked onto his right arm, and an anchor on his left [3]. Both would have been chosen to signify the voyage across the seas to Van Diemans Land or the penal colony of Australia.

Natural physical features were also noted in the convicts’ records, characteristics such as hair and eye colour, their stature or any scars they may have. Alsop’s physical description includes ‘2 Brown Moles on left Jaw’ and how he was ‘Stout made’ [3]. Below is the original account of the convict Thomas Alsop that is from a logbook that would have been filled with many convict records.

These records also provide a timeline of Alsop’s sentence in Van Diemans Land, from when he first stepped onto the Moffatt up until his long awaited return home to Staffordshire, England in 1850 [1]. According to an online archive, he committed more offences whilst he was in Van Diemens Land; he refused to work, stole cattle and was found in bed with a female prisoner. Despite these scandals, he was still given a conditional pardon in November 1848 which meant he would be free to roam within the boundaries of the colony but was still forbidden to leave. However, in February 1850 Alsop was granted a full pardon meaning he was a completely free man as he was able to return to his homeland.

Convicts’ need to memorialise themselves shows a great ’emotional motivation’ (Donnelly, 1997, p.25) put into the manufacture of these tokens, especially as they were essentially ‘condemned to a social death’ (Tindel, Greiner, Hallam, 1997, p.45) [7]. A great example would be Thomas Alsop, an illiterate man on a low income as a brick layer [1] who had to commission the love tokens he gave to his loved ones. This intense need ignites the tokens with a ‘human resonance and enables them to “speak”‘ to the people they have been gifted to (Donnelly, 1997, p.25). It is this resonance that is possibly what the convicts desire, the impending doom of being shipped off to an unknown land with unknown people probably would have given them a sense of belittlement, so their search for a commemoration lies in these coins. Giving the gift of a love token was clearly extremely important in providing comfort for those sentenced to transportation; the love token is reassurance that their loved ones will always remember them. According to Donnelly, this custom became so popular that it became ingrained into the Victorian culture. The ‘sentimentality, nostalgia and romance’ of the tokens meant they permeated ‘all aspects of cultural production from literature and the arts to the popular press’ (Donnelly, 1997, p.25), an idea which supports their significance.

The need to give these sentimental tokens and engrave them with names, their sentence or trial date and a short message to the loved one it was given to begs to question if these tokens are not necessarily just out of love but also out of defiance. This could be defiance of public authority, the systems or people that enforce this authority or the people that are above them in the middle and upper classes who do not share their wealth. For some people sent to the colonies, their crimes come from acts of poverty, the need for food for themselves or their family is so great that they resort to stealing loaves of bread. Is a sentence of transportation for life really necessary for such petty crimes? By anchoring their identity into these tiny cartwheel pennies it means that the convicts are never forgotten about, so if there sentence was indeed unjust the tokens serve as a reminder for the cause of their crimes.

According to Maxwell-Stewart, nineteenth century convict narratives are the most ‘authentic’ (Maxwell-Stewart. 1998. p.77) way of understanding convict culture. He states how ‘the one thing they [convict narratives] do tell us is that convict and popular culture overlap’ (1998, p.79). This means there is continuity between convict and the Victorian society’s popular culture, also showing how the state of the society affects the numbers of criminal convictions. In 1833, criminal convictions peaked with 7000 transportations, a great number that still would have been consistent for years after meaning Alsop would have endured some of the worst transportation conditions.

http://www.maritimetas.org/collection-displays/displays/over-seas-stories-tasmanian-migrants/convict-colony

After the convicts gifted their love tokens to their chosen loved ones, it was then for the journey to the colonised land they were sentenced to. This could have been either Van Diemans Land (or Tasmania as it is called today), which was the case for Mr. Alsop, or Australia. Above are the blueprints of a convent hulk for the convict transportation ship ‘Anson’ [4]. The hulk of the ship has been divided into many small sections built around a possible communal space towards the rear end of the ship. The conditions were obviously very cramped as can be seen from the etched rectangles within each section of the hulk which appear to be the plan for where the beds will go. However, this is a two-dimensional blueprint so at first glance this may not seem as bad because it gives the impression there can only be a maximum of seven people per section. But it is more likely that due to the sheer amount of people these convict ships were transporting across the seas, these beds would have been stacked to allow two or maybe even three beds to be stacked on top of one another. Alsop would have been in this exact position, squashed into a giant hulk with around four hundred other convicts to endure the months over the seas to a foreign land.

Ultimately, the commemoration of members of society who were perhaps misunderstood or were unjustly trialled meant their love, their experience and their final gesture before separating from their loved ones were immortalised. For Thomas Alsop in particular, we can see from his original convict records that the simple act of stealing a sheep did not only leave him giving a piece of himself to his mother, but also to history, proving the great amount sentiment that went into forging these tokens.

Primary Sources:

[1] Love token image and information: http://love-tokens.nma.gov.au/search/2008.0039.0141?q=1833

[2] https://convictrecords.com.au/ships/moffatt/1834

[3] https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=fasai00818

[4] Image showing HMS ‘Anson’ convict hulk blueprints: http://www.maritimetas.org/collection-displays/displays/over-seas-stories-tasmanian-migrants/convict-colony

Secondary Sources

[5] Rogers, Helen. 2015. https://convictionblog.com/2013/11/15/tattooing-in-gaol/

[6] Donnelly, Paul. Australian Victorian Studies Journal. 1997. vol. 3. no.1. pp 23-27.

[7] Tindel, Claire. Greiner, Ainslie. Hallam, David. ‘Harnessing the Powers of Elemental Analysis to Determine the Manufacture and Use of Convict Love Tokens—A Case Study’. 1997. pubs. 2015. vol. 36. pp. 44-55.

[8] Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish. ‘The Search for the Convict Voice’. Tasmaniam Historical Studies. 1998. vol.6. pp.75-89.